021: BEN MACARTNEY - Chief Surf Forecaster at Coastalwatch

Available On All Platforms:

Show Notes for The Surf Mastery Podcast: The Art and Science of Surf Forecasting with Ben Macartney

What if understanding the science behind waves could help you catch the best waves every time? In this episode, surf forecaster Ben Macartney reveals the secrets of predicting and scoring perfect surf conditions.

From great circle paths to local bathymetry, every wave you ride is shaped by a complex set of factors. Whether you're planning your next surf trip or mastering your local break, Ben's expert insights will help you connect the dots between surf forecasts and real-world conditions.

Learn how to analyze swell charts beyond the basics to uncover hidden gems at your favorite spots.

Discover why understanding wind direction, period, and secondary swells is critical for predicting surf quality.

Gain exclusive tips on using live wind feeds and buoy data to refine your surf planning.

Hit play and unlock the forecasting tools and techniques you need to take your surfing to the next level.

Ben has been the Head forecaster at Coastalwatch for ten years. In this episode, he explains how waves are made, what he looks for when making surf predictions, dispels some common misbeliefs about reading synoptic charts, describes some of the nuances of swells and most importantly educates us on how to find the best waves. We also talk about how secondary and tertiary swells affect the primary swell and your local break. If you have never looked at a synoptic chart, isobar map, satellite image etc, then this episode may be a little confusing (unless you are in front of google & can look up the referenced images). Below are some links to some introductory tutorials that will get you up to speed pretty quickly. Most of the references are based on Australian, and Indonesian surf.

Notable Quotes:

"Waves travel along great circle paths, following the curvature of the earth, which is why storms far below Australia can still send swells to the East Coast."

"The difference between a great session and an average one often comes down to understanding subtle shifts in swell direction, period, and local wind conditions."

"Waves thin as they spread across vast distances, but their power remains—it’s how a storm thousands of miles away can still produce clean surf."

"Keep trying, keep exploring, and keep learning. The more you observe and experiment, the more you’ll score."

"Owen Wright’s top-to-bottom surfing is a masterclass in precision and power—it’s clean, critical, and inspiring to watch."

Show Notes:

Surf Forecasting Workshop April 2017 - http://www.coastalwatch.com/surfing/21138/victoria-find-out-when-your-local-will-fire

Surf Forecast Glossary - http://www.coastalwatch.com/surfing/13106/surf-forecast-glossary

Surf Forecasting Tutorial - http://www.coastalwatch.com/surfing/forecasting-tutorials

Great Circles - http://www.coastalwatch.com/surfing/177/forecasting-tutorial-great-circles

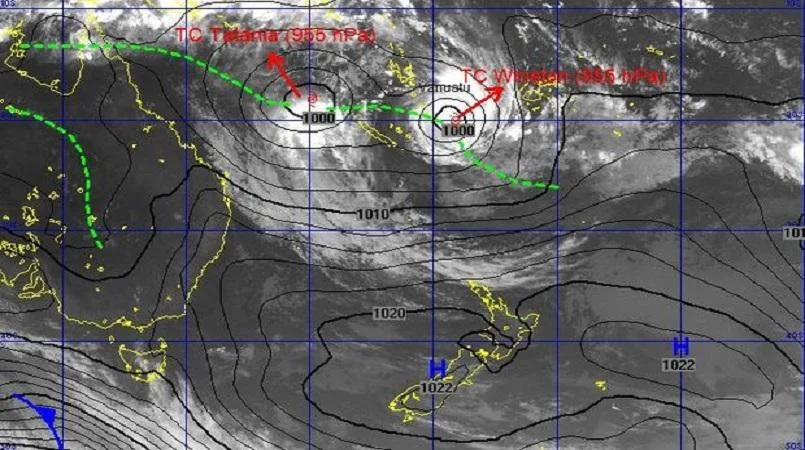

Tropical Cyclone Winston

East Coast Low

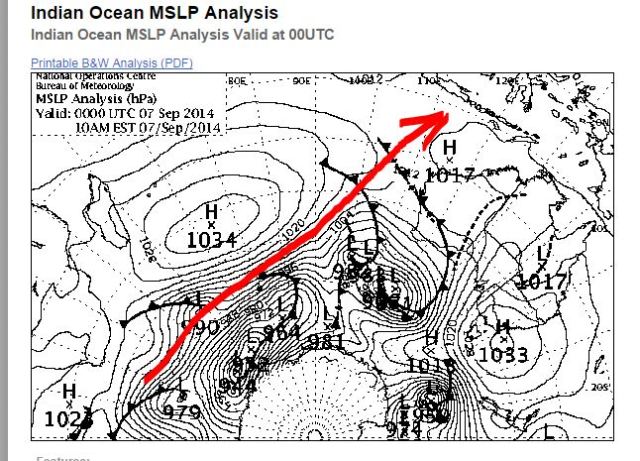

A long stretch of fetch pointing to Indo

Thundercloud Swell June 2012

NOAA - http://www.noaa.gov/

http://www.bom.gov.au/

Coastalwatch Forecast - http://www.coastalwatch.com/surf-forecasts

Key Points

Waves are primarily generated by wind at the sea surface, not by tides or currents.

The key factors for wave growth are the strength, length, and duration of the wind fetch.

Storm systems with a combination of low and high pressure systems generate the strongest wind fetches for wave growth.

The orientation and movement of the storm system relative to the coast affects the swell direction and size.

Secondary swells and wind swells can interact with the primary swell, affecting wave quality.

Local bathymetry and geography influence how swells refract and focus at specific surf breaks.

Swells follow great circle paths due to the Earth's curvature, allowing remote swells to reach distant coastlines.

Atmospheric pressure changes can affect sea levels, impacting surf conditions at reef breaks and slabs.

Observing and understanding local swell patterns is crucial for predicting surf conditions accurately.

Outline

Wave Generation by Wind

Waves are primarily generated by wind at the sea surface, not by tides or currents.

The interaction between low and high pressure systems creates wind gradients that generate waves.

While low pressure systems (cyclones) are often associated with strong winds, high pressure systems play an equally important role in wave generation.

The pressure gradient between high and low systems is what drives wind formation.

Fetch Concept in Wave Formation

A fetch is a key concept in wave formation, defined as the length of water over which wind blows in one direction for a given time at a given speed.

Three critical parameters of a fetch are wind speed, size (length) of the fetch, and duration.

The constancy of wind direction and speed over time compounds wave growth.

Role of Tropical Cyclones in Swell Generation

Tropical cyclones alone often don't generate significant swell due to their small geographical area.

It is the interaction between cyclones and high pressure systems that creates broad, stable wind belts capable of generating substantial swell.

For example, Tropical Cyclone Winston in 2016 generated significant swell not from its core winds, but from a broader area of easterly winds set up between the cyclone and a high pressure system.

High Pressure Systems and Swell Generation

The stability and negligible movement of high pressure systems can be the primary driver of swell.

This phenomenon was seen in recent East Coast events where a big high pressure system with a deep trough below generated significant swell without a stereotypical rotating low pressure system.

Swell Direction Determination

Swells spread radially from their source, but the main swell direction is determined by the most consistent stretch of wind around a weather system.

The orientation of high and low pressure systems determines the alignment of the fetch and the resulting swell direction.

Importance of Wave Period in Swell Propagation

Wave period is a crucial factor in swell propagation.

Higher wind speeds generate higher wave periods, allowing swell to travel and radiate more effectively across ocean basins.

Wind swells with shorter periods dissipate quickly and are more susceptible to headwinds and currents.

Influence of Fetch Orientation and Low Pressure Movement on Swell

The orientation of the fetch to the coast, distance from the coast, and movement of the low pressure system all influence swell generation and propagation.

A low pressure system moving away from the coast generates less swell than one moving towards the coast, as the swell-producing winds have less time to act on the sea surface.

Captured Fetch Phenomenon

A 'captured fetch' occurs when the strongest winds move in the same direction and at the same speed as the waves being produced.

This results in phenomenal wave growth over short periods.

Calculating Wave Speed

Wave speed can be calculated by multiplying the wave period by 1.5.

For example, a 20-second period swell travels at 30 knots in deep water.

This relationship allows forecasters to estimate swell arrival times by measuring distances on maps and dividing by the calculated speed.

Factors Determining Wave Period

Wind speed, fetch length, and duration all contribute to determining wave period.

Strong winds (40-60 knots) blowing for 24-48 hours can generate a big, long-period swell.

However, lower strength winds (35 knots) blowing for several days can also produce high-period swells, albeit not as high as stronger winds.

Interaction of Multiple Swells

Multiple swells often interact, creating complex sea states.

Primary swells may be accompanied by secondary or tertiary swells, which can significantly affect wave quality and surfing conditions.

For example, a clean, long-period ground swell may be disrupted by shorter-period wind swells, creating less ideal surfing conditions.

Impact of Multiple Swells on Different Breaks

Beach breaks may sometimes benefit from multiple swell interactions, creating peaky conditions with numerous take-off spots.

In contrast, point breaks or reef breaks may become less favorable due to these interactions.

Role of Local Geography and Bathymetry

Local geography and bathymetry play crucial roles in how swells interact with coastlines.

Factors such as headlands, bays, and offshore trenches can focus or disperse swell energy, creating unique conditions at different spots along a coastline.

Effect of Local Winds on Surf Conditions

Local wind effects can significantly alter surf conditions.

Coastal geography can create pockets of offshore or variable winds in certain areas, even when the prevailing wind is onshore.

For example, nor-northeasterly winds can become cross-offshore at Tamarama due to the headland's effect.

Atmospheric Pressure and Sea Level

Atmospheric pressure affects sea level, with low pressure systems allowing the ocean to expand and creating higher than normal sea levels.

This effect can be particularly noticeable during East Coast low pressure systems.

Seasonal Differences in Breaks

Some breaks in South Australia are known as 'winter breaks' or 'summer breaks' due to the seasonal differences in atmospheric pressure and resulting sea levels.

Great Circle Paths and Swell Directions

Swells follow the curvature of the Earth along great circle paths, which can lead to counterintuitive swell directions over long distances.

For example, westerly winds in the South Atlantic can generate swells that reach Indonesia after traveling over 6,000 nautical miles.

Long-Range Swell Forecasting

The East Coast of Australia can receive ground swells from remote areas southeast of New Zealand due to these great circle paths.

Understanding these paths is crucial for accurate long-range swell forecasting.

Swell Attenuation Over Distances

Swell attenuation occurs as waves spread out over vast distances, thinning the energy and reducing wave heights.

However, long-period swells can still travel enormous distances with minimal energy loss in deep water.

Consistent Methodology for Analyzing Forecast Data

Develop a consistent methodology for analyzing forecast data, sticking to the same data sets and tools for comparison over time.

This approach builds confidence in interpreting forecast information.

Significance of Secondary and Tertiary Swells

Pay attention to secondary and tertiary swells, not just the primary swell, as these can significantly affect wave quality and surfing conditions.

Building Knowledge Base Through Observation

Observe actual conditions and compare them to forecasts to build a knowledge base of how different swell and wind combinations affect local breaks.

Utilizing Tools for Comprehensive Understanding

Utilize tools like wave trackers, detailed written forecasts, and live cameras to get a comprehensive understanding of current and upcoming conditions.

Exploring Different Spots Based on Conditions

Be prepared to explore different spots, as conditions can vary significantly even over short distances due to local effects and swell interactions.

Managing Expectations in Surf Forecasting

Manage expectations by understanding the complexities of swell generation and propagation.

Recognize that many factors contribute to actual surf conditions beyond simple swell height and period predictions.

Transcription

It's a beautiful thing about wave growth. It can be described mathematically.

Welcome to the Surf Mastery Podcast. We interview the world's best surfers and the people behind them to provide you with education and inspiration to surf better.

In the inner, you've got all this chaos happening. There's waves bouncing around everywhere.

Michael Frampton

My guest for this episode is surf forecaster McCartney. Is a surfer from Bondi Beach in Sydney. Rips, as you can see by the photo on Instagram, charging a nice big left-hander there. But professionally, Ben is the head forecaster for Coastal Watch and has been for the last 10 years. In this episode, we learn how waves are formed and how to predict them, really, and we go into some of the details about how to read maps and some of the nuances of swell formation. If you have never looked at a synoptic map with the intention of thinking about what waves are coming from a system, then the second half of the interview might lose you a little bit. So you'll either have to be in front of Google or on the Coastal Watch website, there is a whole section on forecasting tutorials that will give you the basics and a lot of visuals. There is links to this in the show notes. Ben is also currently traveling around Australia doing a forecasting workshop with Nick Carroll. There's one in Victoria on the 15th of April. I'll put details to that in the show notes as well as on the Facebook page. Relax and learn a little bit more about surf forecasting.

Ben Macartney

Okay, all right.

Michael Frampton

So, where do waves come from?

Ben Macartney

From wind at the sea surface. It's not to do with the tides of the moon. It's not to do with currents as such. It's 99.99% wind-generated, yeah. And everything we look at, the way we study the forecast, the way I guess, analyze the forecast, it's all in the context of surface wind over the ocean.

Michael Frampton

Strong wind is usually typically associated with a cyclone or a low pressure system.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, that's right. And I think in all surfers' minds, that's the, you know, the golden synoptic feature that we look for, if you like, the stereotypical cyclone or big low, deep low pressure. And they are what generate wind at the sea surface, but it's always in conjunction with a high pressure system on the other side. And I've come to realize over the years that often it's the high pressure that's just as important, if not more important than the low that you're looking at. It's the gradient between them that generates the wind in a way. There's this imbalance in the atmosphere in air pressure, and that the rebalancing process is what generates all this wind. So to just say, yeah, it's all about low pressure systems is a bit of a misnomer or a misconception in a way. I can think of a lot of good examples, especially when you talk about tropical cyclones. In isolation, tropical cyclones generate incredibly strong clockwise winds over a really small geographical area, like a category four or five system can produce wind speeds of 100 to 150 knots, which in kilometres is almost double that. So incredibly strong. If you think about the winds we see here on the coast that can do damage to houses, they're just 35, 45 knots, 35 to 50 knots. You think about wind speeds that are double or triple that, that's incredible forces at work. But yet in isolation, a tropical cyclone out to sea somewhere is just like a storm in a teacup. It won't actually generate much swell of note unless it is within immediate proximity of the coastline. So to go back to surface wind at the sea surface, we describe it, these winds, in the context of a fetch. A fetch is a length of water over which a wind blows in one direction for a given timeframe at a given speed. And I have, you can say there's three key sort of parameters we look for with wind at the sea surface. That's the strength of the fetch, the actual wind speed, the length or size of the fetch, how many hundred nautical miles it might cover or thousands of nautical miles even, and the duration. So how long it lasts for. And by that I mean that wind blowing in the same direction over that same surface area. Because that's what compounds wave growth is that constancy or that continuum of wind blowing in the same direction and the same speed. So yeah, so to go back to a tropical cyclone, if you've just got these clockwise winds, you know, blowing round and round within 300 nautical square miles, it's the resulting swell that emanates from it is actually dissipates really fast and it doesn't really amount to much. What generates the swell? We saw this with tropical cyclone Winston last year. You know, that storm system set up over the, did a huge anti-clockwise loop around the Southwest Pacific and its life cycle took in about 26 days. It's almost a whole month. So I did this tour of the Southwest Pacific and for the first half of its life cycle, it kind of generated a bit of swell and weakened and moved away from Australia. And then it did this big loop and came back to the West across Fiji and re-intensified. And it was at that point that it set up, it wasn't that the core winds itself that were the real source of swell. It was this broader area of easterly winds south of the storm that was set up in conjunction with a big high over the Southwest Pacific. And it's this, it's almost like the hare and the tortoise, you know, it's this broad, stable area belt of winds that isn't even that strong. It might just be compared to the core wind speeds. It's only things like 25 to 35 knots, like a fraction of the core wind speeds, yet it's set up over, you know, a thousand nautical miles. And it remains in place for several days. And that's what generates swell. That's those winds constantly blowing. And it just compounds the size of the deep water swell hour by hour, if you like. And that's what I look for in forecast storm systems is I'm not just looking for a low or a cyclone or a really deep system. It's always about the balancing effect between the high and low. The last event we just had here on the East Coast, it was basically just a big high pressure system with a deep trough below. There was no real, there was a closed low on it, but your stereotypical, you know, rotating low pressure system just, that we look for with the tightly spaced isobars, it didn't exist. It's really, it was really about the stability of the high pressure and that negligible movement of the high over the Tasman Sea that is actually the real driver of the swell.

Michael Frampton

So if there was a really deep low, let's say it was sitting in between New Zealand and Australia, people often think that there would be that pressure system would have a ripple effect. Whereas in there would be a big circle of swell that would emanate out everywhere from the center of that low. Is there any of that going on?

Ben Macartney

Absolutely. Swells do spread radially from their source.

Michael Frampton

But that's not the main swell that comes from there. It's more, you're looking for where the most consistent stretch of wind is around that system. Yeah.

Ben Macartney

I guess you look at storm systems in the context of what they're interacting with. So i.e., a high pressure system. Now that hypothetical high pressure system will sit up against the low at a certain angle. The high might come in from the southwest, or it might be supporting it directly from the south. It can even be coming in directly from the west. And it's all about the orientation of the high and low in the, you know, which way they're aligned. Because that will determine the alignment of the fetch and which way the belt of winds, which is the wind fetch, is pointing. So if you have, you know, a big high coming in from the west and our hypothetical low over the Tasman Sea is rotating, then the resulting gradient is actually south to north. Because it's interacting with the eastern flank of the high. It's hard to take all this in without a visual reference. Yeah.

Michael Frampton

We'll give listeners a visual reference maybe on one. Yeah. They can look up. But so there might be a deep low in between New Zealand and Australia. And we've got some ripple effect swell sort of going everywhere from the chaos. But the main swell is gonna be where the compression between the two systems happens. And then there's a long stretch of consistent wind. Yeah. And that's gonna be the main swell.

Ben Macartney

And the swell will be driven in that direction, the same direction as the wind. And of course, there will be radial spread. So there will be swell spreading out either side of that primary directional band. The core direction of all those winds. Within it, you've got all this chaos happening and there's waves bouncing around everywhere. And so it's not a wave growth and wave formation is not just a linear thing. It doesn't just, you know, go one, two, three, four feet over X number of hours. It's kind of, there's all this chaos in there and the physics involved in calculating it. I mean that, yeah, it's depending on the size of the storm. It's a bit like a bomb going off in the sense that you've got all this energy being released at the surface and it's spreading radially. And there's varying degrees of how waves propagate and spread across ocean basins that are really contingent on wind speeds. Higher the wind speeds, the higher the wave period and things like that. And the higher the wave period, the more effectively this swell will travel and radiate out across an ocean basin. Conversely, a really weak fetch that doesn't exist for, that only sets up for a short timeframe and is only short in length will probably only generate a wind swell which is really susceptible to things like headwinds and currents and will dissipate before it can travel out beyond, you know, 500 to 1,000 nautical miles. They dissipate very quickly, these deep water swells. It's not just the fetch. We're looking at the strength, duration, et cetera, as I discussed before. It's the orientation of the fetch to the coast and the distance of the fetch to the coast. There's all these other little nuances like which way is the low and therefore the fetch moving. That has a huge influence. If a low is retracting away from the coast, then those swell-producing winds are moving backward away from, say, the coast and therefore they're not acting on any one area of sea surface long enough to generate a large swell. I've seen this a few times this year, actually, and I think we're going to see another example this week. This low that's forming off the coast on Thursday, it's forming east of Bass Strait, and it's just going to slip away to the east or east-southeast even. And because of that, even though it's a substantial low, those swell-producing winds are retracting and so they don't have the time to actually work on one area of sea surface long enough to whip up a particularly large swell. We'll still get waves. It's kind of like a two- to four-foot swell, maybe three to four feet at its peak. Whereas if that same low-pressure system happened to be tracking north into the Tasman Sea or back towards the coast, it'd bring the swell-producing winds along with the swell being produced, if you like, and that has an incredible compounding effect on the swell. So the strongest winds, when they move with the swell being produced in the same direction, and if you happen to have it travel at the same speed as the waves being produced, then that's called a captured fetch, and that's where you get phenomenal wave growth, just within, you can have 20, 30-foot seas within 24, 48 hours, stuff like that.

Michael Frampton

So how fast do waves move?

Ben Macartney

Well, a very easy way to figure that out is to multiply the wave period by 1.5. It's a beautiful thing about wave growth. It can be described mathematically. And that's why we describe fetches in nautical miles and wind speeds in knots, because there's a direct relationship between them. So in this case, if you had a wave period of 20 seconds, you multiply it by 1.5, that's 30 knots. That's the deep water speed of a group of waves. That's how fast it's traveling through deep water. Obviously, that changes as it approaches the coast, waves. As they begin to feel the sea floor, they begin to shoal and decelerate. So they lose speed, substantial speed, before they actually, and as they break, they're virtually, they're almost standing still for a moment, I guess. But yeah, that's one way to, it's a very easy rule to follow. If you're looking at a wave map, a chart, and you're looking at a wave period map, particularly on the big ocean basins, like the Indian Ocean and Pacific, where you can, you know, swells have potential to travel for over a week before they hit somewhere. If you take a snapshot at a certain point in time, at the, say at the limit of the model run, which is seven days usually, you can look at the leading edge of a wave period band and calculate the distance to a given location. It might be Indonesia or Western Australia, say if you're in the Indian Ocean, or it might be New Zealand if you're in the Pacific. And if that leading edge of the swell is 20 seconds, then you know that it's traveling at 30 knots. So you can measure the distance on Google Earth and then just divide it to see how long it'll take to arrive. Because if you measure it in nautical miles, then nautical miles divided by knots gives you the number you're looking for in hours.

Michael Frampton

The wind speed determines the period.

Ben Macartney

It plays a big factor, but again, it's in the context of the length of a fetch and the duration, how long it's blowing for. So you might have 50, 60 knot winds blowing, like in a tropical cyclone, they might blow over one area for three hours before the system moves away. And so it's not gonna have much of an effect. But if you've got a big belt of winds that's really strong, 40 to 60 knots, and it's blowing for even just 24 hours or 48 hours, you get a really, you get a big swell out of it and long period swell, yeah. But by the same token, if you get a lower strength fetch of 35 knots, even if that blows for several days, you'll still get a high period swell, not as high. So yeah, there is a direct relationship between wind speed and period, but it's always in the context of the size of a fetch and its duration. So there's no simple recipe there. You can't always just say, yeah, we're gonna get a long period ground swell out of this because the winds are 45 knots. It's all in the context of those other factors. Okay, yeah.

Michael Frampton

The main swell is where the longest length of fetch is pointing to, would be this direction of the swell. But then you've got, like you said, you've got these ripple effect swells coming out of the system as well. Does that explain the smaller, less perfect waves in between the big sets on a day? Where you might have a swell, let's say you've got a two metre swell at 15 seconds, and then there's three waves every five minutes. But then there's all these other waves that aren't as clean coming in as well. Are they potentially coming from the same system?

Ben Macartney

Not necessarily, but if you assume they are, again, there's a lot of factors that go into that. If you talk about long range sources, like say a swell for Indonesia, where you're out at G-Land and there's six to eight foot sets, but in between there's really constant three to five foot waves. And it's like, they're probably exhibiting different periods. So the reason you can have a sea state like that, where you have all these different waves breaking different heights, and I think it boils down to the characteristics of a storm system and the winds within it. So usually from my experience anyway, it's the largest waves that are generated, the big six to eight foot set waves carry the longest intervals. They're generated at the height of the storm system's life cycle. So say that occurs when the storm is 1,500 miles from Indonesia and you get 45 knot winds over 24 to 48 hours, stable fetch generates this ground swell that's hitting at 16, 17 seconds and they're the six to eight foot sets. What happens after that? Say the storm's travelling northeast towards Western Australia and it starts weakening. Suddenly the fetch has moved several hundred nautical miles further to the east and northeast and the wind speeds are 35 knots, 35, they've dropped 10 knots, but the fetch is still in place and maybe the alignment's changed a tiny bit, but it's still, it's actually closer to Indonesia than the strongest fetch area was at the storm's inception. So what you effectively have is a new fetch. It's the same storm, but it's generating a new swell and that new swell will come in at lower periods of say 12 to 14 seconds and it won't be as big because 12 to 14 seconds swell will dissipate more, it's, the wind speeds aren't as strong so it hasn't whipped up as much swell, the storm's weakening, but what you can see happening is both of those swells arriving at the same time because say if the storm system has moved ahead of the ground swell it's produced, which is pretty common, they accelerate out to the east or northeast and they generate a much broader but weaker fetch within closer range of Indonesia, then suddenly you've got this additional mid-period energy in the mix and that can mix in with the anteceding ground swell and that's a really common effect of storm systems, big broad scale storm systems that generate, that have multiple stages in their life cycle. Like some of these storms will intensify like below Madagascar and generate a fetch like that, super strong, then that lasts about 24 hours, it'll weaken for maybe a day or two and it'll still be generating 35 knot winds and then it redevelops as it comes in over the southeastern Indian Ocean below Indonesia and you get a renewed fetch of 40 to 60 knots or something and because of all those life cycles in the systems they can generate sort of unique swells within the broader swell itself and I guess that's what we don't necessarily see in some of the wave modelling we look at. It's all a simplification of a very complicated sea state. So when we say, yeah, look at those peak intervals, it's 17 seconds and wow, it's an approximation of the peak energy in the water based on a mathematical set of rules that's been applied by a person. A person's gone, okay, well we're gonna measure the top 30%, 35% of waves and what their average wave period is and assign that as the peak height and period. But you can alter those variables and you'll get very different readings and that's why some models will show slightly different readings for wave period and height, things like that. For instance, if you look at significant wave height on a swell map, that's very different from swell wave height. Significant wave height is the wind swell added to the actual underlying swell. So that's the total sea state. So you can have significant wave height might be 50 to 60 feet over the Southern Ocean somewhere, but that's just chaos. Within that, you've got all this multitude of different waves exhibiting different periods and frequencies, if you like. So I think it's always something to keep in mind when you look at the wave modelling. It is a simplification of reality. And that's where analysing the fetch can give you a jump. Where you get a fetch that's travelling towards Indonesia over several days, if we stick with Indonesia as the example here, and you see that it's gone through several phases in its evolution. It started out at x speed, as I mentioned before, and changed to y speed and the location of the fetch has changed, but it's all generating swell for Indonesia. What that means is that you're going to have a much more energetic swell event with all these waves in between. So while it's six to eight foot at G-Land on the sets, in between it's just constant three to six foot waves. Really a lot of water moving down the reef, a lot of wave action on the reef. That's one of the beauties of surfing Indonesia is its exceptional exposure to storm systems over the Indian Ocean. Now the converse of that, a good example, is where you have a really zonal-oriented fetch. A zonal is west to east. So in the instance where you've got a dominating high pressure over the central Indian Ocean, and it's suppressing storm activity. So the storms tracking below that high are pushed further south into polar latitudes, say below 50 degrees south. Well, that's really, they're all polar fronts and lows moving through. The winds generated between that dominant high and the lows, the storm track beneath it will be westerly. And so they're actually not aimed at Indonesia, they're aimed at Tasmania and New Zealand. The primary swell band is aimed away to the east, away from Indonesia. But what you get is this radial energy spreading off that storm track. But what you get from that is a much more discreet swell. It's more of a vector. That doesn't make sense. It has less spectral density, is a good way to put it. There's less diversity in the wave trains moving in. What you'll get is a high period pulse arriving, spreading radially off that primary swell. And it'll just be a fraction of the deep water swell. So instead of six to eight foot sets, it might only be three to four foot. And because it's only those high period waves that make it to Indonesia, all you're seeing is the sets. In between, it'll be really like calm. And that's where you get these long lulls. They'll be like, you can be out there and in 10, 20 minutes, there's hardly any waves breaking. And then when the sets come, there might be three to five waves. And it's really, it's beautiful because there's not a lot of movement in the water. But it's that ground swell alone that's arriving. It's not all these interacting wave trains arriving at once, you see. So that's something to keep in mind. When you look at a wave period band spreading out across the Indian Ocean, you see it's got peak periods of 20 seconds. You go, wow, look at that ground swell. It's gonna be amazing. Let's book a flight. It's kind of like, hold your horses because what underpins, what else is it telling you? If you look at the storm system, what's the full story? And you can sort of say that it might not be all it's cracked up to be. Yeah. You go, bit disappointing.

Michael Frampton

To Ulus, there's a hundred people out and there's three waves every 10 minutes. Yeah, something like that. A.

Ben Macartney

And that's how you can really differentiate, I think, is by looking at a storm system and asking yourself, well, is it aimed directly at Indonesia? Is it travelling towards Indonesia or is it slipping away? How long has those winds been blowing for? A really good telltale sign of a major swell event is when you can see that these wind fetches are aimed at Indonesia, but they last so long that the blobs of swell you get on the wave charts, and they're not just purple, but they're purple over a much broader area. When you get those really expansive areas of seas and swell in the significant heights, like 40 to 50 feet, you know that that's another way of deriving, well, this storm system has been in place for days at a time, the winds are strong to generate seas of that size, seas and swell of that size over such a vast area, it's gonna be significant. Whereas if you get those much smaller storm systems, where there's a little purple blob in the middle and it's fanning out off it somewhere, then obviously it's not going to be as significant by the time it arrives. Yeah, I've seen plenty of good examples of that. You know, the swell that hit Cloud Break all those years ago, they call it, you know, the guy made the movie Thundercloud, all the big wave guys were there, they were meant to be running the event, and you had all these Hawaiian guys paddling in on nine, 10 foot boards or whatever into 20 foot perfection, pretty much. That storm system just set up was complex, slow moving, and it set up over the, you know, below the Tasman Sea in New Zealand for many days at a time. And because it was just a slow, low pressure gyre, if you like, there were just multiple lows rotating through that system that was supporting these incredibly strong wind speeds for days at a time. And so what you sort of have is this huge burst of 45 knot winds for 12, 24 hours, and it eases a bit, but you've got this massive sea state in place, and then the next low comes through and just adds to it. And that's what's sometimes referred to in forecasting as the step ladder effect, where you get very large, complex storm systems rotating in a large, low pressure gyre. You can see these in effect when you look at Southern Ocean synoptic charts, like synoptic charts that take in the entire Indian Ocean or the entire Pacific, and you can see these, what some people refer to as the long wave trough, where you might have a super active area of storm activity that manifests as a gyre. So it's like a big parent system, and within it, there's a multitude of smaller lows rotating through it. And they're the big storm systems to watch out for if you're planning a trip somewhere, if you're looking just to target a swell and go and find some big waves. It's those broad scale systems that last for days at a time and move slowly. They can really, they piggyback on each other. One low will generate 30-foot seas. The next one that comes across adds to it, et cetera. So yeah, it's interesting.

Michael Frampton

So if you just look at the charts and you see a swell that's three metres at 18 seconds, it might just be one of those swells where there's only three waves every 10 minutes. So it's pretty important to not just look at the charts on Coastal Watch, but to actually go and look at the paragraph that you've written on the forecast as well.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, absolutely. I guess that's where the written discussion can give you an idea of what's really going on, rather than just looking at the wave chart or graph that will give you a generic height and period. And they're good snapshot indicators. There's no doubt that a virtual buoy of any sort can give you a reasonably good idea of what might happen. But to really, for decision-making purposes, if you're thinking of jumping on a plane or deciding whether or not to take two big boards or just three short boards, things like that on your trip, I think it's really helpful to drill down into the actual storm system itself and see what's going on. By that, yeah, that means looking at synoptic charts and forecast surface winds and satellite images of surface winds. They're all, I guess that's the stuff I look at on a daily basis just to get a handle on swell potential. You can definitely give yourself an advantage, I think, just by spending a bit more time looking at the origin of a swell.

Michael Frampton

And learning about it. Yeah. So what about, let's take the example of a local Australian East Coast forecast or system. And sometimes it can be, let's say, a two-metre southerly swell at 15 seconds. And there's these really clean lines coming through, the reef breaks light up. If there's a good bank, you get some good clean waves at a beachy. And then a couple of weeks later, you get another 15-second southerly swell at two metres. And it's kind of wobbly and bumpy and the reef breaks aren't really breaking properly, but then the beach breaks kind of light up and you don't need as good of banks to have peakiness. Yeah. But looking at the graph, the swell looks the same, but can you explain the nuances between? Yeah.

Ben Macartney

I mean, there's a lot of potential nuances that can make that happen. And a big one is secondary swells. At any given time, there's often more than one swell in the water. And sometimes you end up with two swells that are kind of competing. And what you can see on a wave graph can be misleading because you might see it's two metres at 15 seconds. But what that doesn't show you is that there's a 15-second ground swell coming in that's two feet. And the primary swell is actually a six foot, so a 1.5 metre swell that's only eight to nine seconds. So what you've actually got is a combination of wind swell and ground swell. But on the chart, it looks the same because they both say they're both coming from the south. It's gonna look the same. Whereas in the first instance, if you've just got just a two metre 15-second ground swell coming in from 180 degrees straight south, then there's no noise. There's none of this sort of additional swell adding wobble into it and adding this sort of bit of chaos into the mix, I guess. It's just a pure ground swell that'll be clean when it arrives. So yeah, I mean, there's a lot of nuances there in that sense. Even the swell direction can have a big impact. The difference between a deep water south-southwest ground swell that's actually spreading up into the Tasman Sea at 190 degrees, which is a little past south-southwest, they will actually, if it's long period, if it's above 15 seconds or more, they can focus into certain reefs and bays and points and generate really big surf while other beaches remain relatively tame. We tend to see that every winter, at least once or twice, where a sizable long period directional ground swell arrives. By directional, it's kind of spreading up parallel to the coast, but there's still a component of that energy refracting back into the New South Wales coast. With any ground swell, there's that spread and some places will just pick it up and focus it. Usually because of the offshore bathymetry, there'll be a deep gully or a trench or something. One of those spots is Depo Bommie. I know from experience that you see photos of it breaking at 10 to 15 feet on these ground swells, and my local beach will be six foot. Bondi, it'll pick up, picks up, in theory, the maximum amount of south ground swell, but it'll just be five, six foot. And then other beaches can just be three to four. And it has a lot to do with the local geography and the coastline and how they interact with that deep water energy. I guess to put that into context, you need to think of ground swells in terms of deep water energy, i.e. how far they penetrate below the surface. So a wave with a period of 20 seconds, it penetrates about 350 metres below the surface.

Michael Frampton

Wow, about a thousand feet.

Ben Macartney

So it's gonna interact with the sea floor so far offshore that you can't actually see where it... So by the time you see the swell, it's already changed because of the sea floor. Whereas a wave period of eight seconds, it penetrates about 50 metres below the sea surface. And so its interaction with the sea floor is much more localised. It won't really react substantially until it hits the beach, almost, before it really begins to feel the bottom. Whereas deep water ground swells will almost react to the continental shelf or reefs, deep water features offshore. And now once they react to those, what are they doing? They're slowing, they're wrapping, they're refracting and doing all sorts of things. They're being modified. And that's where you get a lot of misconceptions. I know from my own experience over the years, seeing a lot of local surfers see a big south ground swell coming in because it's already turned to face the beach much further offshore. It looks like an easterly swell. And a lot of people will say that. They'll say, it's meant to be a south ground swell. This is coming in straight out of the east. And so they dash off down south to Maroubra because Maroubra is the place to be when it's an easterly swell. And it's not even getting in there properly. It's kind of almost flat down the south end and four foot up the north end or something. And they go, they scratch their heads and go. I've seen that happen. I've had guys come to me and go, we thought it was an easterly swell but Maroubra is not getting it. And it's like, that's a straight south ground swell at 17 seconds or something. That's what it does. And you can have these similar effects at your own local area. You might see a particular swell arriving at a particular period and direction. And it can actually, it can be confounding. You can go, wow, it's not really getting in here or it's really focusing in this other spot. I've seen it happen out the front here at Av where deep water southeast ground swells and stuff seem to focus on that reef that's right out off the southern cliff. I think one of the boys has paddled out there and surfed it once. Have you heard? Everex. Is that what they call it?

Michael Frampton

Yeah.

Ben Macartney

Yeah. And I've seen like in some of these ground swells, particular swells, that reef just focusing these sets. And it's like, there's no one surfing it. But you can see it's gotta be like six foot plus. And yet on the beach, there's hardly any sets coming in. And it's like four foot or something. And you go, what's going on there? And it's just the bathymetry in action in a particular swell. And you can get similar effects everywhere where swell react to certain parts of the sea floor given at a particular, on this continuum of period and direction, which is complex. Even slight shifts in the direction can change the effect. And then there's the tide, things like that compound what the local effects you have. If you get unusually big tides, suddenly like we saw, I think it was late last year or earlier this year with the super moon and the huge tides that we had were about as extreme as they get. On the extreme low tides like that, suddenly you can have a bathymetric feature offshore that's suddenly much shallower than it usually is. And you've suddenly got a ground swell reacting to it, whereas normally it passes over the top of it. And there's all this sort of stuff that can happen with swells, I guess. And that's where just your local observations can really pay off, just knowing years and years of observing your own local breaks and knowing how they react in — exactly.

Michael Frampton

In combination with looking at charts as well, though. Yeah.

Ben Macartney

So that's it, that's how you learn, is you know if you can analyse the forecast swell and look at the data that's showing. On the real wave buoys offshore, they actually give you real-time indications of deep water swell and period. Compare that to a virtual buoy run. And yeah, you've got to be able to — I mean, some people write that down as a guide. I used to.

Michael Frampton

Yeah.

Ben Macartney

Yeah. Yeah, I've heard of a few guys just year off, you know, to accumulate this knowledge year after year so they know what to expect. And they've got precedence.

Michael Frampton

Because there can be a big difference between a 181 degree swell at 15 seconds at two metres and then 184 degrees of a swell that has a period one second less. Yeah. It might look really similar, but if you start looking at the details and you go, no, that's actually quite a different swell because last time we had a swell like that, I went around the corner and thinking that there would be waves at the beach around the corner, but there wasn't. So now I know just to stay here because that swell is getting in here. I know from experience, there's no point driving 10 minutes up the road because that angle and that period comes into that beach at a kind of weird. And that's because of, you know, the nuances in the direction, the period, and the bathymetry as well.

Ben Macartney

For sure. Yeah.

Michael Frampton

I went through it when I was, when I started surfing, there was no surf forecasting things. It was, I used to take a photo of the conditions, especially if it was good at a break, and then I would cut the ISOBAR map out of the paper and stick it on the back. Yeah. And then, you know, I started journaling like. Yeah, I used to learn which beach to go to based on the map and the marine forecast.

Ben Macartney

That. And that's a great way to do it.

Michael Frampton

Yeah.

Ben Macartney

Yeah. That's a clever way to do it, I think. And, you know, in the pre-digital age, when before the internet was just, all you had was the weather charts and the paper and —

Michael Frampton

Yep, yeah. And the marine forecast on — Yeah, so there's those nuances about bathymetry and changes in swell direction that affect waves at your local break.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, that was it. That was about it. But yeah, it's certainly changed since then.

Michael Frampton

Yeah.

Michael Frampton

But there's what we talked about before was the secondary swells as well.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, that's right. And they play a big factor, I think. Easy to overlook when you're looking at a primary swell on a chart and you're focused on the deep water ground swell. Often what you don't see is some short period swell that's in the mix, or even one or two of them. You might have some residual northeast wind swell from the day before, and then a southerly change comes through before the arrival of the ground swell, and that whips up a small south-southeast wind swell or something. And suddenly you've got all this noise mixed in with the ground swell, and it can really, you know, take the shine off these events. Or perhaps sometimes it might not matter, and other times you go, this isn't what I was thinking, even though the next day on the arrival of the ground swell, the winds are offshore and everything looks like it should click into place. You've got these additional wave trains that can throw a curveball into the mix. Yeah.

Michael Frampton

I've been caught out in the past where you see one of these clean swells coming, and you go to a point break or a reef break, and it's all funky and wobbly and weird because of the secondary swell interacting. But then you go to a beach break, which might not have banks per se, but because the secondary swell is interacting with the other swell in such a way, there's all these A-frames up and down the beach.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, it can be really favorable for some spots rather than others. You know, for me, it brings up the characteristics of different swells and how I know at Bondi, where I grew up surfing, short-period swells can just be, you know, just be fantastic. You get these really particularly large short-period swells, like a three-metre swell that's only eight seconds, and it turns into a really sort of peaky fun park with all these different lefts and rights. And I've seen it change, like, in the space of one day to the next, where the period jumps up to 10 seconds the next day, and it turns into what it's always been and always will be, which is mostly a closeout. Yep. And you hear guys say, wow, the banks have gone, you know, but it's kind of, the sand's still there, it's just the swell characteristics have changed and it's interacting with the bathymetry, with the sandbanks, differently. You know, these waves will, an increase in period will increase the wavelength, so you have longer swell that's feeling the bottom in deeper water and reacting to the whole sandbar rather than the gutters and rips. Things like that. So yeah, it's interesting.

Michael Frampton

Yeah, I guess that's kind of exaggerated in the corner of a beach where there's a bit of a headland, you see the, they call it wedging, when the first wave of the set refracts off the rock or whatever and hits the second wave of the set and makes that wave peel and it's more powerful. Yeah. That's a really obvious way to look at what we're talking about. But Tom Carroll said something in a previous interview, is that getting better at surfing has got a lot to do with really paying attention to the details. Yeah. And that's one thing that helped my surfing a lot. And so I really started looking at, okay, I'd look on the chart and go, okay, there's a primary swell here, but there's a primary southerly swell, but there's a secondary nor'easterly swell. And so when I'm surfing, I'm looking out, where is that nor'easterly swell? I'm not just trying to get in rhythm with the bigger sets. I wanna know, I wanna get in rhythm with both of those swells and really look. I found it really helpful to look at the charts and at the period and the direction and size of that secondary swell. And it just, when you have a look, and even tertiary swells as well. So when you have a look at the forecast and the charts, when you go surfing, you've got an idea of what to look at so you can learn to see these other waves in the water when you know what you're looking for. Absolutely. This is something else I found important, another sort of correlation between looking at, having this obsession with surf forecasting.

Ben Macartney

And it makes things really, I think that's where we're really lucky on the East Coast. We have this incredible diversity in different swells in terms of, on the swell spectrum of direction, period, and height, we get this incredible variety. We really do. Whereas a lot of the big west-facing coasts around the world, it's kind of more of a staple, mostly long period swells out of the southwest or west-southwest, varying degrees from there. But I mean, the West Coast a few years ago got a big northwest cyclone swell. And that was the first one that apparently a lot of the locals had ever seen in like 30 years. Whereas for us here, we get this incredible diversity and yeah, it makes life really interesting. I've had similar surfs like that where you get these two swells interacting and they have incredible effects when on a beach break somewhere, when they both combine. It's kind of rare, but when you see it happen, they're really unique.

Michael Frampton

Yeah. It's rare to see it really like to play to place up, but at the same time, it's always in play. Yeah, it is. As well. And I find that's the difference between, you see the surfers, they go out and they just seem to catch all of the good waves. And you're like, you catch a wave and it's just fat and it doesn't peel. And then they paddle out again and they catch the other one. I think the difference is they're really aware of some of the details of how other swells, not just secondary and tertiary swells, but the way the wind's interacting with the surface of the water.

Ben Macartney

Which waves are bouncing off a rock and wedging. Refractions, exactly. Which ones aren't. Yeah, that's the power of observation, I guess. And when you apply that power of observation in the context of knowing about what swells are in the water, it can give you a big jump.

Michael Frampton

What about, so we've got all these nuances locally about how certain swells can seem somewhat similar on the chart, but actually on the day, very different, depending on slight differences in period, angle, and of course the effect of other swells. But there's something similar going on with winds as well, I find. Like there's a big difference between a nor-easterly and a nor-east-easterly, for example. Because the winds can kind of just, they just seem to swirl around different bays. And can you end up with pockets of almost offshore or light variables in corners and places?

Ben Macartney

As well. That's why a straight easterly or anything from an easterly, the easterly quadrant, is just a surf wrecker for just about everywhere because it can't interact so much with any headlands or valleys or geography, if you like. It's just gonna come straight into every exposed bit of beach and just blow onshore. Whereas the effects of the coastal geography on different winds is phenomenal. And it's a beautiful thing. There's a lot of places. I know my local, Tamarama, when the winds are nor-noreast, it's virtually offshore in there. You've got this huge headland that sticks out and the wind curls around it and comes down in through Mackenzie's and Tamarama and it's cross offshore a lot of the time. Or just cross shore. And it's just like a little miracle of nature. Yeah. And there's other really good examples around here. And I guess that stuff, I don't, it's not stuff that I incorporate into daily forecasts because it's such a granular thing in terms of every bit of coastline has its own idiosyncrasies in that regard. I've seen, one of the most unique ones I've seen is at Whale Beach, where it can be blowing west-southwest, and the wind curls around onshore.

Michael Frampton

Yeah, I've seen that.

Ben Macartney

It's unbelievable. Like in theory you're going, wow, this is like perfect conditions. Like the winds are offshore at a certain speed. And yet when these sets come in, there's this weird rippling onshore effect going on. And a guy explained it to me recently as downdrafts coming off that steep valley, the winds, as it comes over the top of a steep valley, it's, you know, it's coming down and curling back in. There was a term for it that alludes me now, but it's not something I study on a day-to-day basis, those local wind effects. But when you observe them, it can be staggering.

Michael Frampton

Yeah, it's good to take note. And on the Coastal Watch website, you guys have the live wind feed.

Ben Macartney

We do.

Michael Frampton

From the airport, is it?

Ben Macartney

Yeah, from automated weather stations, from the Bureau of Meteorology. They have, you know, usually update every half an hour or even sooner. So.

Michael Frampton

They're worth looking at, because the wind can be forecast as a nor-east-easterly, but it might actually be a nor-nor-easterly in reality. And sometimes it's hard to tell from, even if you live at the beach, whether what's going on up the road. But if you keep an eye on those live feeds, you get more of an idea of what the wind's doing in real time compared to what the forecast.

Ben Macartney

Is. Absolutely. The forecast models, especially GFS, which drives a lot of the forecast data that you look at, that's a global forecast system that is freely available from the US Navy, from NOAA. You know, it's not particularly granular. It's picking up gradient winds and isn't factoring in the local effects of the coastline and smaller weather systems necessarily. And that's where on Coastal Watch, we've got APS2 model running, which is from the BOM for the first 72 hours on our forecast winds. And it does factor in a lot of the local land effects. So you'll see it will pick up early morning offshores before a southerly kicks in, things like that. But yeah, it's always interesting. I keep an eye on the live winds religiously. Because winds, they don't obviously follow the forecast modelling precisely. You can have onshore. I saw it, we saw it over the weekend where the onshore east-northeast flow starts to, it'll just die out for a few hours. Suddenly you get this window, like when we paddled out at ABB the other day, actually, and the winds suddenly drop off to five to 15 knots for about an hour or two. And you've got this short window. It's like a little miracle where the gradient has just slackened over the region temporarily, where you can get some really fun semi-clean waves before the wind comes back up. Yeah, and that happens a lot, when you watch these weather systems unfold and you have a gradient wind in place where it's just blowing out the surf at 15 to 20 knots all day. If you keep an eye out, there are these windows that'll appear where the stability of the gradient fluctuates and you suddenly have a drop in local winds. I guess that's one reason why so many hardcore surfers don't even worry so much about forecasts. They just go, just check it. Just check it every day. Just watching it.

Michael Frampton

That's good. If you have the time to have that luxury, that's awesome. That's right. What's the difference between a wind swell and a ground swell? Is it a line in the sand? Yeah.

Ben Macartney

Well, it's a loose line in the sand and it really comes down to wave period. And wind swells are locally generated, usually within close range of the coast. The wind speeds usually aren't as strong. And so the swell's more disorganised and not necessarily as big. You can get massive wind swells, of course. But yeah, the real differentiator is period. And anything that's below 10 seconds is pretty much regarded as wind swell. And anything above that, more above 12 seconds, you can talk about as ground swell. I think in my forecasting notes, I usually make reference to mid-period swells as the sort of in-between. Because I think there is an in-between, where there is some deep water energy present, but it's not particularly strong. So I just call it mid-period energy. And that generally means anything from nine to 12 seconds, I guess, that bandwidth. There's some substance there, but it's, yeah. It's the magic number, wave period, absolutely.

Michael Frampton

What about, you know, sometimes, I don't know whether this is just because our attention is drawn to the fact that it is raining, but sometimes when it starts raining, the waves kind of stop.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, I've noticed that as well. I've noticed.

Michael Frampton

Can you explain that?

Ben Macartney

I can't necessarily explain that, no, I don't. I haven't thought of a — well, what happens in big, when you get a lot of low pressure, then it actually takes pressure off the sea surface and the sea surface will rise.

Michael Frampton

You know. I mean, does atmospheric pressure affect?

Ben Macartney

That's where you get storm surges. So when we have big East Coast lows, I don't know if you ever noticed this effect, but the sea level will be higher simply because if we have low pressure over us, then the pressure exerted on the sea surface is lower and therefore it allows the ocean to sort of expand in that area, swells. Yeah, and I've seen that effect with big East Coast lows on plenty of occasions where I've gone down to jump off the rocks and it's like a mid tide or a low tide and it's like a massive high tide and you go, what is going on here? I can't even jump off the rocks in my usual spot and guys are jumping off in completely different locations.

Michael Frampton

That makes sense now. Yeah. Because I've always kind of maybe thought that especially in terms of height, that tide prediction is never really quite right. But now if I think about it and take into account atmospheric pressure, that could explain that discrepancy.

Ben Macartney

It does, big time. Because I guess day in, day out, we don't see a lot of variation from around 1000 to 1030 HPA. And that difference won't, I don't think it'll have a real noticeable effect on the sea surface. But once it really starts to drop, if you've got low pressure over the coast and it's well below 1000 somewhere, then you can see that effect can be quite pronounced. A guy from South Australia told me once that there are, down there, winter breaks and summer breaks. That these places that break only in winter and others that break only in summer simply because of that pressure difference that you have between winter and summer.

Michael Frampton

That just due to the height of the water? Yeah.

Ben Macartney

Yeah. With the onset of big frontal systems and low pressure, you get this, yeah, totally different characteristics.

Michael Frampton

So atmospheric pressure doesn't really affect the swell. It's more the sea level.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, I mean directly over the coast, over the actual place where you're surfing, the atmospheric pressure doesn't. Yeah, that's right. But it can definitely have an impact on sea level where you get extremes in pressure. Yeah, I've never thought too much about the converse of that and whether extreme high pressure can actually keep the water level down. Yeah, should look into that. Because I've, I guess because I've always observed it during East Coast lows, it's something I became aware of a long time ago and read about since. But the converse should in theory be true to a degree.

Michael Frampton

Changes in atmospheric pressure would certainly make the extremes a little bit off what's predicted as well. Yeah. It would suppress or allow more movement. Therefore the timings could be slightly different.

Ben Macartney

And perhaps, you know, that's just another little factor that can make one day different from another when in theory they should look the same. All those little factors all add up together to produce a unique day.

Michael Frampton

Yeah, especially at some certain reef breaks and slabs where the actual water level on the reef is so important. And it's, there's low tides and there's low tides, right? So we've really got to consider how much water is on the reef, not just whether it's a low spring tide or a low neap tide. There's much more to — although tides is probably a whole nother, it's a whole nother discussion, tides.

Ben Macartney

It. Yeah, there can be, I think.

Michael Frampton

Something interesting you mentioned last time we spoke was that looking at a two-dimensional map can be deceiving because the earth is three-dimensional and you referenced great circles.

Ben Macartney

Think it is. I think it is. But.

Michael Frampton

Could you summarize those maybe?

Ben Macartney

Yeah, I guess if you grab a sphere, like a ball that you might sit on at work instead of a chair, and if you try and draw a straight line on it, you kind of can't. It's always going to be curved. Any line drawn on a sphere will have a curvature. And I guess that's what we take for granted when we look at the swell maps, is that over long distances, swell will follow the curvature of the Earth. And these paths, these curves along the Earth, are known as great circle paths. And if you Google it, you'll come up with a lot of stuff about aeronautics and aerial navigation, because pilots use them to navigate across continents, et cetera. They'll fly across these great circle paths, but swell travels along great circle paths. Effectively, it's traveling in a straight line, but it's following the curvature of the Earth to a distant location. These great circles really only come into effect, I think, when swells are traveling more than 1,000 nautical miles. But it has quite incredible implications. And these are sort of the sort of things I only became aware of years after getting right into swell forecasting. The fact that a giant storm system below the Great Australian Bight that's generating even west-north-west winds can actually give us a ground swell here along the East Coast. And it's really counterintuitive when you look at a weather chart. And I used to tell people, once I discovered all this stuff, I'd tell people, I'd say, we're getting a ground swell. Where's it coming from? It's coming from below South Australia. They'd look at me like I'm an idiot. And go, what are you talking about? You're not making any sense. And in the forecast notes, I'm saying there's a huge westerly swell below Tasmania and South Australia is actually gonna give us a south ground swell. And how does that work? Well, if you open up Google Earth and you use the draw function, you can draw a line from anywhere along the East Coast down into the Southern Ocean. And you'll start to see as you get down into polar latitudes, how that line curves along the Earth's surface. It's quite a nice effect. And if you scroll out from the screen and so you're looking at the entire sort of ocean basin, the Tasman and even the broader, the Great Southern Ocean, you can really see these effects in play when you mess around with the line function on Google Earth. It's a really useful way to analyse swell windows, to look at what land masses might be acting as shadowing or blocking certain swells. So you can see the limits of our swell window south of Tasmania. But it's staggering — like some swells will, if they're big enough, even though the primary direction of that giant swell somewhere over the Indian Ocean or below Australia might not be along a great circle path, the refracted energy will be. So the sideband energy radiating out from that swell source can travel along a great circle path to our coastline. And although it will arrive at very small heights, often just a fraction of a — even just a fraction of a foot sometimes. So, you know, half a foot, a half a foot swell at 20 seconds, stuff like that. And yet it's originated thousands and thousands of nautical miles away. I guess you call these, often in forecasting, I think of them as theoretical swells because the wave modelling is picking it up and it's showing on all the charts. It actually, you can see the wave period band moving up into the Tasman Sea, but it's so small that it won't have a palpable effect on surfing conditions. It will be superseded by a different swell that's generated much closer to the coast. But yeah, they are fascinating. And they have real, really palpable effects for places like Indonesia and even, you know, the West Coast of America and Hawaii, obviously, but anywhere where the swell travels, where long period swells can travel for thousands of nautical miles, it has an impact, yeah. A good example is Indonesia. In theory, you can have ground swells generated over the South Atlantic arrive in Indonesia. So if you get westerly winds over the South Atlantic, if the swell's big enough, it'll travel some over 6,000 nautical miles to arrive in Indonesia. And that'll be over seven days later. It's — I tracked one last year and it arrived at two feet at 20 seconds or something. Yeah. They can come from a long way away. And yeah, again, that's a beautiful thing about the East Coast. We can, every once in a while, we get these really remote south, southeast ground swells from not just below New Zealand, but well southeast of New Zealand. And these really remote corners of our swell window that every once in a while, you'll get a big fetch set up down there and they generate fantastic waves for the East Coast, like a southeasterly direction with a long period can just be fantastic. And I've seen, you don't see many of those, but it's just another example of the variation we can get. You know, years ago, I think Mike Stewart, the bodyboarder, he chased a swell from New Zealand to Tahiti and then onto America and then eventually Alaska. And that's how far these things will travel.

Michael Frampton

Wow. So you can actually beat it on a plane.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, you can beat them on a plane. Yeah, if your flights are scheduled nice and tightly, yeah, you can get the jump on these swells and be there just in time to surf a spot the next day. And, you know, that was done in the nineties, Mike Stewart and I can't remember who else it was. Maybe it was just him. And more recently, I think some other guys gave it a go and chased a swell across the Pacific basin. And — but I think the Pacific Ocean is really the only one where you can feasibly do that. Perhaps you could do it in the Atlantic, but it's known as — it's been proved possible that a polar swell in the Southern Hemisphere can be surfed in Alaska. And that's vast distance. I haven't measured it. That's the, you know, it's a pole to pole almost. And that it's testament to the incredible efficiency with which deep water ground swells will traverse deep water. They move with virtually no friction. They move, they're unimpeded until they reach a landmass. And the thing that really makes them dissipate as they travel is the attenuation of the swell, is the actual spreading process. If you think about the swell at its origin, a swell line at its origin, as it moves up — I read this the other day and it's a fascinating idea. If you think about, just to illustrate the effects of swell spreading and the effects of the globe on the swell, if you imagine instead of the South Pole, there was a big storm there. It was just a massive low pressure system where the South Pole is. And it was a huge low just generating giant swell. And that swell was just radiating out from that point zero. At the South Pole, every direction you look, it's north. So all the swell is traveling north along every longitudinal band. But those longitudinal bands diverge from the point you leave point zero. So they're diverging. And it follows that the swell diverges as it approaches the equator.

Michael Frampton

Thin out. And then potentially if it was unaffected, theoretically, once it had passed the equator, would it then slowly compress and get bigger again?

Ben Macartney

That's an interesting — I haven't actually thought it through that far. I haven't, but that is a fascinating idea. If you think about the — perhaps it would compress. If you approach the North Pole, they're actually — the lines of longitude are compressing. Would the swell then regather into a smaller and smaller area? It makes sense that it would in a way.

Michael Frampton

If it was unaffected by —

Ben Macartney

But you'd think perhaps you'd need some assistance from some bathymetric assistance in a way. I don't know. It's a really complicated idea. But yeah, I'm probably beyond my level of knowledge for sure. But we do see those effects in Indonesia, those incredibly long swell lines that arrive along the reefs and beaches there that just stretch as far as the eye can see, basically. The wavelengths are incredibly long and that's sort of a by-product of this thinning effect of the swell — is the attenuation of the swell.

Michael Frampton

Fascinating. Yeah, it is. A lot to it. So let's summarize a little bit maybe. We talked about the nuances of secondary swells, tertiary swells, bathymetry, atmospheric pressure. There's a lot going on with scoring waves at both your local and surrounding beaches as well as surf trips. So I just would urge from personal experience, and I would just urge people, just to keep an eye on not just the charts, not just the swell charts, but look at the secondary swells or tertiary swells and not just at the start of the day but the end of the day as well. Yeah. So just go, what did the forecast look like and how were the waves? And if your local beach really lights up, maybe even jot down some of the details as well as looking at the winds as well. You mentioned the actual buoys.

Ben Macartney

The actual wave.

Michael Frampton

You guys list that on Coastal Watch. That's there on Coastal Watch. All the wind charts, the live winds, the wind predictions are all there, as well as your take on, you know, what's the word? Like taking all of this theory into something practical because like we said, you can have a swell that looks good but it might just be a bunch of lulls.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, that's exactly.

Michael Frampton

Right. Make sure you look at the paragraphs that he writes when he breaks down what the maps are showing as well. Is there anything else that I've missed that people might be?

Ben Macartney

There could well be. I mean, I can usually just talk on and on about the various aspects of wave propagation and, you know, storm systems and all the nuances. But I don't know, I guess I think it can be a powerful thing, as you said, to make observations in your own right of swells and then reflect on what the forecast data was telling you and what swells were in the water, what the conditions were like, and having a knowledge base can really allow you just to manage your expectations in a way about what to expect rather than, you know, just seeing, you know, high periods at three metres and going, come on, I'm going to take a week off and we're going to go down the coast and find perfection. Just to know that it's not necessarily all it's going to be cracked up to be. I mean, I guess for me, you know, with surfing, a big part of it is just that, just managing expectations. And because over the years, I've seen so many potential amazing storm systems, and when it does arrive, you kind of go, of course, there's this secondary swell or the wind hasn't been offshore long enough and there's still all this chop left over from yesterday or even just the sandbanks are really straight. And there's so many factors that come into play in that sense. I think, you know, it's... I think there's two important things for me. One is keep trying, keep getting out there, drive down the coast, drive up to the next beach around the corner and keep looking, because even if you think it's not going to be that good or probably, it can be. The more you look, the more you'll score. I think the more you go and put yourself out there and get out of your comfort zone, I think that's one rule to follow.

Michael Frampton

And just quietly, we can look on the cams.

Ben Macartney

That's right. We can look on the cams. And.

Michael Frampton

You know, if it is pumping somewhere, Coastal Watch users will put photos up as well. So we can get an idea of what's happening around our area and down the coast just from looking at the cameras and user photos as well.

Ben Macartney

Yeah, there's plenty of that. There's no shortage of resources there. One of the final things I'd say is that there's so much potential data and sources of information to look at. I think it's just important to develop your own methodology and stick to it. In other words, you know, I mean, ideally Coastal Watch has all those tools on offer, whether it's the wave tracker where you can monitor wave period against swell and the different wave trains, as well as the detailed stuff I write. There's a lot there. But whatever it is that you use to forecast is to — I don't know — is to sort of stick with it. And that way you're constantly referencing the same data sets. I think that can be quite handy. Something I've stuck to over the years, and I do look at a lot of different things, but I have a sequence where I compare them to each other and it gives me an underlying impression of what's going on. But yeah, so I think it's very useful to cross-reference, but if you do it in a rigorous way, it can really give you a lot more confidence in what it's telling you.

Michael Frampton

Just before you go, what's your favourite surfboard at the moment?

Ben Macartney

I guess it's Pyzel. Pyzel. It's a Bastard. Yeah, that's the name of the board. I'm not calling it a bastard. But yeah, that's probably my favourite one that I've had for a while now.

Michael Frampton

Yeah. Do you have a favourite surfer?

Ben Macartney